#OE1 - Movement 101

This is probably a good place to start for the first real individual-topic development post, since the movement mechanics of this game are really fundamental to everything I'm trying to do here. I'll try not to wax on about the design philosophy and the "why" behind it all in this post (though I'm sure to do that at some point), instead I'll try to present the "how" as clearly as I can. I will also be skipping over a lot of the complexities that have emerged around this system as it's become more developed so you can get an idea for the basic concepts first.

A Broad Overview

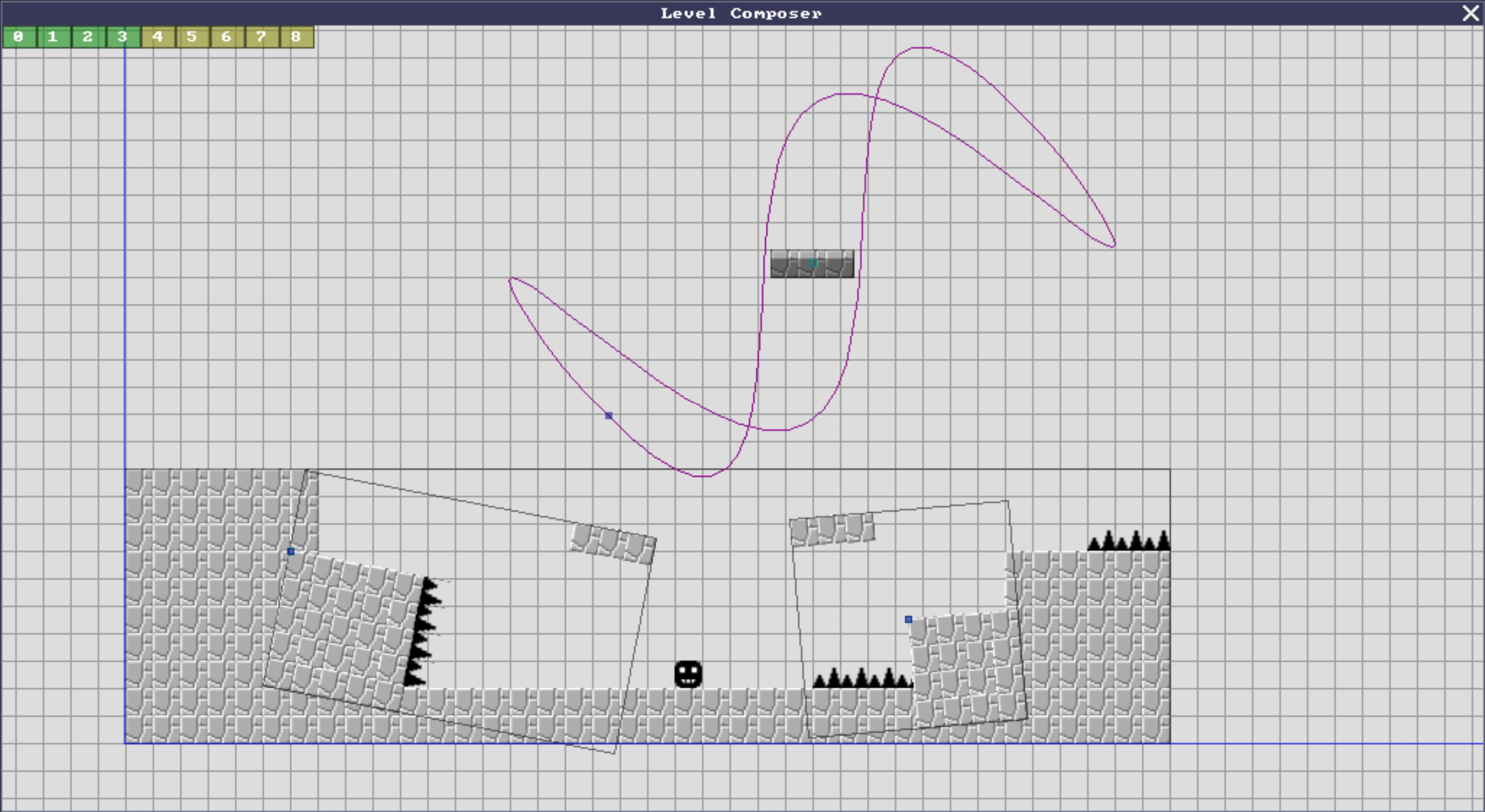

Let's start with the basics. The game world is made up of several individual tilemaps I call "tile layers". Tile layers come in all shapes and sizes, and they all have somewhere to be (that is, they have some defined location in the broader world). Knowing where a tile layer is gives us the power to do all sorts of things like render it on the screen and let the player interact with it. But many tile layers don't just sit still, they move around giving us all kinds of fun obstacles to contend with. Some of them even spin too.

But in order to move, tile layers need to know where they're going. In this game, we like to keep things predictable, so tile layers (basically) always move along a predetermined path. In order to accomplish all sorts of interesting types of movement, we construct these paths from simple primitives. These primitives of movement are called "movement components".

Each movement component describes a simple path. This can be a line (or series of lines), circle, ellipse, curvy line (or series of curvy lines), or the path traced by a pendulum. These are the five basic types of movement components: - linear splines (straight lines) - bezier splines (curvy lines) - sine movement (circle, ellipse, figure-eight) - pendulum - rotation

Rotation is a bit of a special case, so we won't really be talking about it until Movement 102.

Movement components generally represent a closed path (one where the start and end point are the same), though this is not always the case. This is because in a platforming game, you usually want motion to be cyclical. This gives the player another chance if they "miss the bus" on a moving platform so-to-speak.

But even if we have a path, we need to know how quickly we are supposed to move down it. We have the "where" but not the "when". So the last piece of our puzzle is to introduce the concept of a timer. A timer lasts for some number of seconds, and if we start a timer when the level starts we can use our progress through the timer to determine where we need to be along our path. For example, if we have a path that is a straight line 5 units long and a 6-second timer, then we know that at 3 seconds we should be 2.5 units down the line (because 50% of our time has elapsed, we have traveled 50% of the distance). The same principle applies for a curvy line or a circle just the same, but instead of traveling a straight line we follow a curve, or a path of any arbitrary shape.

Like I mentioned about the paths above, we usually want movement to by cyclical. So instead of simply starting a timer and then stopping it when it's expired, we allow it to loop on its n-second long cycle.

Using some simple math, we can determine our progress through any given cycle using only the global time since the level began.

time_in_cycles = global_time / cycle_time;

current_cycle = floor(time_in_cycles);

progress = time_in_cycles - current_cycle;

We divide the global time by the number of seconds per cycle to get the number of cycles which have elapsed since start. The integer portion of this value is the number of whole cycles completed, and the fractional portion is the percent progress in the current cycle. We can then use this progress value to determine our offset in space by interpolating along the path of our movement component.

As I mentioned above, we can also build more complex types of motion from our simple movement primitives. This is as easy as adding together the offsets of multiple movement components. If we apply the same movement component to two tile layers, and then add a second movement component to only one of the tile layers, the apparent result is motion of one tile layer relative to the other.

Hopefully you've understood everything up until now, because we've essentially worked backwards to explain how the system works. In practice, we start with the timers, then update our movement components to obtain our position offsets, and then finally apply those offsets to our tile layers. It is important to keep in mind the relationships between these objects. Each movement component has a one-way dependency on a timer (but many movement components may share the same timer), and each tile layer depends on any number of movement components to determine its final position for that moment in time. And at the very source of it all, each timer is simply a product of subdividing the global time into smaller sections.

Implications

We can use this top-down control to our advantage, as it gives us a singular point of control over the entire level. The global timer may be the single most important variable in the game, because it ultimately determines the location of all the tile layers in the game world.

If you're an astute reader, you've likely noticed that we can compute the positions of all tile layers in the game discretely. That is to say, we don't depend on any state that carries over from the previous frame(s). The game update loop proceeds linearly from the most basic constructs in the game to the most complex, bootstrapping from almost nothing to the state of the world and all of its complex interactions every single frame. We can compute the positions of all the tile layers at any given time just as easily as computing them for the next frame, and the entire operation of the world is deterministic. I'll save the diatribe on time manipulation shenanigans for another post, but needless to say, there will be some by the time this game's development is all said and done.

Anyways at this point (once we know the locations of all the tile layers for a given frame), we can finally run our player update loop and allow the player to interact with all the tile layers that make up the world. In a game based around movement and the player's interactions with it, we definitely want to know more than just position however, we also need to know velocity. In most games, its trivial to determine the velocity of an object because the world operates in a relatively continuous manner. In the traditional model, forces apply some acceleration on an object which changes its velocity, and then the velocity is applied to position on each frame. Since we determine position from scratch every single frame, we actually have to work the opposite direction and derive our velocity from position. When time is operating normally, we just subtract our current position from our previous position in order to determine the instantaneous velocity of our tile layers. Again, we'll talk about when time is not operating normally in another post. We never really need to know the acceleration of a tile layer, but it could be derived similarly if the need arose.

Though it's probably a bit unconventional, hopefully you can start to see some of the utility in such a system of movement. I know I said this post would mostly focus on the "how" and not the "why", but I would be remiss not to outline just a few of the reasons for using this system.

Firstly, the amount of possibilities you can acheive by composing the simple movement primitives is actually insane. I have yet to see a platforming game which does as much with moving platforms as can already be done in this engine. Of course, it's a lot of work to present each of those ideas in an interesting and approachable way and if your game is not just about jumping on moving platforms, I can understand why you would put your focus elsewhere. Lucky for me, this game is basically just about jumping on moving platforms, so I get to explore all ten million ways of doing that.

Secondly, and this reason is related to the first, it gives far more control to the designer of a level to express the particular ideas they want to express, without needing to get caught up on what should be trivial side effects. Designing levels using this system of timing means that we are thinking about movement less in terms of speed and moreso in terms of time-to-complete, which is a subtle but meaningful difference. Instead of having two platforms which move at a given speed, and then trying to coordinate their movement relative to once another by moving them around or changing their speed manually and hoping for the best, we can be assured of a platform's location at critical points in time. I can't tell you how many times I've had platforms de-synchronize while modding The End is Nigh because one of them has to move one tile further than the other and cycle time is a product of distance and speed rather than speed being a product of time and distance. I really do not care if a platform moves at 4.5 tiles/second or 5.2 tiles/second, so long as it stays coordinated with the other elements of the level.

Anyways, that about wraps up all I want to write for this post at the moment. I'm bound to have forgotten something but either I'll just add that back in her elater or mention it in the next post. I hope you were able to get something out of this and it was worth your time, so until the next one, have a good one.